The Black Box is Broken: The Modern Critique of the Grammys

Guest author Thomas Merrilees, Pitzer ’26

“The Grammy is the only peer-presented award to honor artistic achievement, technical proficiency and overall excellence in the recording industry, without regard to album sales or chart position.” – The Recording Academy.

This is filler. This statement is a mere placeholder meant to justify the Grammys’ arbitrary role as the ultimate arbitrator of music. Most corporate mission statements are vague, slimy, and self-congratulating, but the Grammys’ statement is unusually specific; for an organization that seems to get near-universal criticism, sticking their neck out like this should be a death sentence. Thankfully for them, nobody reads corporate mission statements, but the Grammys are far from unscathed. Historically, the organization has mostly faced criticism through what I will call the “Black Box” argument, which generally sounds something like this: ‘I don’t like the Grammys because I don’t know how the voting process works, and I don’t know who the voters are.’ The machine of the organization is opaque, only disclosing inputs and outputs. A 2020 New York Times article about this topic is headlined, “Can the Grammys Be Trusted? (Caramanica)” Another article from Vox is titled, “The Grammy voting process is completely ridiculous” (McKinney). Consistently mentioned in the Black Box argument is the fact that many of the artists themselves are outspoken against the Grammys, like The Weeknd boycotting the show altogether after being snubbed in 2021, Frank Ocean not submitting Blond for consideration in 2016, or Ariana Grande refusing to perform in 2019 (Mamo). The primary focus of these more traditional sources is on authority, and stories upon stories of the mysterious voting process, artist dissent, and all-around corruption are targeted at that authority. This approach has its merit, but it doesn’t exactly resonate with those born with the internet at their fingertips. I googled “F*** the grammys” and the second result was an online thread from Reddit’s subcommunity on the late rapper Mac Miller, with top comments saying “Honestly. I will never get over them awarding Cardi B the award over Mac…”, “They’ve been a joke for a bit now, especially after Macklemore won best rap album over Kendrick’s GKMC”, and “they snubbed the weeknd all of last year too” (r/MacMiller). These people do not focus onauthority, they focus on the content. We are all too familiar with media through a mysterious Black Box, even ones that are widely hated like Google or Meta. People use YouTube and Facebook anyways, despite the veil hiding the algorithms and the data collection. The Grammy hate has always existed, but it is now morphing from criticizing values of older media to criticizing values of newer media. The problem is no longer that the box is black; the problem is that the Black Box doesn’t work properly.

The role that the Grammys play is not unique, or even rare for that matter. Anyone can judge music, and I would go as far as to say that everyone, consciously or unconsciously, verbally or nonverbally, judges music. Something as simple as thinking “I like this song” or “this song is too loud” or simply tapping your foot is a judgment. We are all critics, all subject to arguably similar material. Apart from your local artists and bands here and there, the music audience is subject to the same subset of music. You and I can both log into our own respective music streaming services and play the exact same song, no matter how well known or obscure. The music industry has undergone convergence, a term that Richard Jenkins uses to describe when a single piece of content can be accessed in multiple forms. Music has long been a converged platform under the guidelines he established: “… media audiences must not simply buy an isolated product or experience but rather must buy into a prolonged relationship with a particular [musician]… the strength of this new style of popular culture is that it enables multiple points of entry into the consumption process” (Jenkins). Audiences don’t just like a song by an artist and leave it at that; they check out the album, they listen to the next album, they watch music videos, they buy official merchandise, they go to shows, they watch interviews, and so on. When describing the outcome of convergence culture through what he calls “participatory culture,” Jenkins talks about the active response of the audience: “The first and foremost demand consumers make is the right to participate in the creation and distribution of media narratives.” There’s very little chance an amateur musician or fan will ever have any cultural impact without going through a major label, but they are still able to change the music. If an artist experiments with a new style of music unlike their existing catalog, they will likely react through their fan reactions: if the new album gets played a lot, if people are sharing it with their friends and buying merchandise, the artist will probably stick with that style; if they get backlash and sell poorly, they will most likely go back to their old style.

Word of mouth is powerful in the media industry; music critics exist just to be professional opinion-havers. Everyone judges music, and critics’ line of work puts effort into that judgment while keeping track of it and spreading it to others. The most popular online music critic, Anthony Fantano, has been directly addressed by major artists dozens of times through social media, song lyrics, and interviews; if Drake himself is angrily messaging Fantano, “Your existence is a light 1. And the 1 is cause you are alive,” using Fantano’s own rating scale of 1 to 10 and then posting a screenshot to twitter, critics most certainly have an impact on the artists (Mier). The internet is an expansion of the idea of participatory culture, where anyone can share their amateur or professional opinion, and exert some influence over the media they consume. Clement Chau pushed this idea of digital interactivity in their paper, “YouTube as a participatory culture”: “Rating videos and commenting are popular activities among teens, and a small portion of teens contribute by posting videos as responses to videos they have viewed, creating a self-generating process” (Chau 71). People are becoming more and more used to a world where their opinions can matter through a system with a complex formula for guided navigation through the site. Everyone counts a little through online Black Boxes like YouTube, Instagram, and Reddit. Authority is irrelevant when everyone can post; quality of content determines value here. The online critic space is just an expansion of online convergence culture tailored to music, embracing the Black Box.

If authority doesn’t matter to newer generations of Grammy-dissenters, then what does? The Grammys position themselves as the top music critics, benevolently deciding what is good and what is not. Again, according to The Recording Academy, “The Grammy is the only peer-presented award to honor artistic achievement, technical proficiency and overall excellence in the recording industry, without regard to album sales or chart position.” In order to judge how well this Black Box is as a critic, the job of a critic needs to be understood. The largest YouTube video game critic, videogamedunkey, speaks on his experience: “You don’t have to see eye to eye on every game to put your trust in someone… a critic’s power relies on the consistency of their voice” (videogamedunkey). He brings up how he hates turn based combat and anime, usually giving games with either of those types a bad score. If he were to give a turn based combat anime game a good or even mediocre review, it allows the viewer to determine that it is likely a pretty good game compared to the others in the genre because his consistency allows his reviews to be comparable with one another. Further in the video, videogamedunkey brings up the importance of originality: numerous Batman(and other superhero) reviews often say that the game “makes you *feel* like batman”, along with blandly written, boilerplate descriptions of the gameplay and nothing more. He remarks, “I can find all this **** on the back of the box, but at least there, it would sound exciting.” If all a review does is act as a medium for the producer of the art to speak for itself, then there is no point to the review. Critics need to provide in order to be effective. As the aforementioned Anthony Fantano said in a video justifying his various negative reviews, “The audience has no reason to engage with you if you don’t challenge their thoughts and their beliefs” (Fantano). Critics do not exist to affirm what you already know; they are an alternative perspective, giving you insight into something you might not have considered or noticed before.

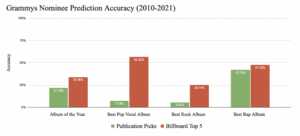

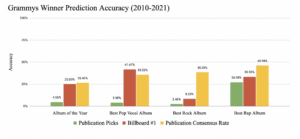

To attempt to answer how effective of a critic the Grammys are, I researched the top 32 publications with consistent album of the year lists from 2010-2021 across four Grammy Award categories and compared them to the Grammy results. I also threw in Billboard’s 5 highest selling albums from their end of year data to see that correlation in comparison. A longer explanation on the particularities of this process is linked here. It is not necessary to understand the data, but it will attempt to answer any questions about the method I used. The graphs with my findings are below:

Publications never even come close to being as accurate as sheer Billboard data when it comes to predicting Grammy nominees or winners. These numbers are genuinely absurd. Ignoring the Best Rap Album category(which I will save for last), publications that professionally review music are completely irrelevant when it comes to predicting Grammys results. There is slight agreement in the nominations of the AOTY category, but anything else is absolutely hopeless. Pop nominations were 8x more likely and winners were 10x more likely to be predicted by Billboard data than the critics whose job it is to review and rate music. The Rock Winner category is a particular standout, with publications only having a staggering 2.46% accuracy rate. As an aside, by the nature of how the Grammys work, the Best Rock Album category is going to be in the top 40 of the highest selling albums of that year. To put things in perspective as to how low the accuracy percentage is in this context, you would have a better chance of correctly predicting the winner of the Best Rock Album category if you were to throw a dart at that top 40 list than to listen to any of the opinions of the very best music critics of that year. AOTY and Pop winners are at least understandable through the influence of high charting music, but there doesn’t seem to be any understanding of the Rock category. The “publication consensus rate”, a measure that simply lists the percentage of publications that agree on the most commonly picked album, was created to address this. If the publication winner prediction was equivalent to the consensus rate, it would mean that the Grammys committee agrees with critics just as often as critics. This could potentially answer whether the low rates for publications and Billboard are due to widespread disagreement or if it is genuinely random. Unfortunately for the publications(and fortunately for my argument), on average 38% of them agreed on what should win the Best Rock Album category. There is popular consensus, but it is just being ignored by the academy. The Best Rap Album category seems surprisingly representative in comparison; critics generally align more with what is popular, and the 46% consensus translates to a 27% winner prediction rate for publications(not great, but certainly good in comparison to other categories). Because of the Black Box nature of the system, the only real way to try to explain this is to theorize. Since only 18% of AOTY nominees and 0% of the AOTY winners over the last 11 years have been rap albums despite the genre being the most popular one in the US, as well as the Grammys having a historically racist record, I believe that the Best Rap Album is overly responsive to critics as a method of shutting out rap from AOTY consideration. Your guess is as good as mine.

Since conversations of this type inevitably revolve around particular snubs, I thought it would be fun to take a break and briefly list a few of the largest snubs and the percentage of publications that theoretically would’ve voted for them to win: Sir Lucious Left Foot… – Big Boi (53rd Rap – 52%), Let England Shake – PJ Harvey (54th Rock – 52%), good kid m.A.A.d city – Kendrick Lamar (56th Rap – 47%), Lost in the Dream – The War on Drugs (57th Rock – 41%), To Pimp A Butterfly – Kendrick Lamar (58th AOTY – 45%), Blackstar – David Bowie (59th Rock – 73%), & RTJ4 – Run the Jewels (63rd Rap – 55%).

Enough data. You get the point. Back to the divide of the argument of the Grammys: why would a person focused on content care about this data while a person focused on authority wouldn’t? The problem to those focused more on authority is not that the results are bad; even if they were, that would merely be the product of a faulty system. If you were to modify the system to their liking, they would expect the results of the data to fully support the Grammys. If the Grammys were to have trust and authority, it wouldn’t even matter to them what some puny little publication had to say about the topic. The Grammy committees are *the* deciders. These results add no fire to the flames of the Black Box argument. Quality of content, on the other hand, does not care about the process, only the output. Someone who spends a few hours per week browsing TikTok, relying on the magic algorithm to spoon feed them content, is not likely to be concerned about how the Grammys work. If it serves its purpose, then the show is just like every other piece of modern media. The data strongly suggests that it does not fulfill its stated purpose as the sole organization that has the capabilities to properly critique music. The generalized critic guidelines from Anthony Fantano and videogamedunkey still apply, even to an award show: if it doesn’t provide anything different from what the audience already knows and believes, what’s the point? If a viewer can have a similar experience from two hours watching an Award Show as they do from five minutes on Billboard, why watch the show?

There is no verifiable consistency in the Black Box, not because the box is black, but because there appears to be nothing inside the box at all; Billboard data goes in, Billboard data goes out. The new hate comes from the uninteractivity and the monotony of the process; there is no action to be taken once the winners are announced because everyone already knows the winners. Critique is meant for refinement and self-reflection, not repetition. My voice when talking about music on YouTube or Reddit or Instagram or any other social media matters to everyone but the Grammys, and the same goes for artists on those platforms too. The Grammys do not appreciate other efforts to arbitrate music. Jenkins spoke on the response of those who control convergence culture to those who try to take part: “Media conglomerates often respond to these new forms of participatory culture by seeking to shut them down or reigning in their free play with cultural material” (Jenkins). Here is the mission statement from The Recording Academy for a third and final time: “The Grammy is the only peer-presented award to honor artistic achievement, technical proficiency and overall excellence in the recording industry, without regard to album sales or chart position.” Old and new perspectives critical of the Grammys agree on their disagreement with the second part of the sentence, but take different issues with the first. The old perspective disagrees with the claimed authority, wanting it to be actualized. The new perspective disagrees with the idea of authority in this space altogether, wanting any claims to it to be disregarded entirely. They want the box to be thrown out, not be made transparent. The Grammys are hated now because they blatantly disregard participatory culture; they have cosplayed the role of the critic at the public’s expense, abusing the interactive nature of music discussion only to tell us what we already know.

Works Cited

Caramanica, Jon. “Can the Grammys Be Trusted?” The New York Times, 26 January 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/25/arts/music/grammys-controversy.html. Accessed 13 December 2022.

Chau, Clement. “YouTube as a participatory culture.” New Directions for Youth Development, vol. 2010, no. 128, 2010, pp. 65-74. Wiley Periodicals, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/yd.376. Accessed 13 December 2022.

Fantano, Anthony. “Negative Reviews Are ESSENTIAL!” YouTube, 15 August 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3I6Qu1E2cNo&list=PLDLuFyMR91wc6YjxrZr0oDE79hDMcwce1&index=297. Accessed 13 December 2022.

Jenkins, Henry. “Quentin Tarantino’s Star Wars?: Digital Cinema, Media Convergence, and Participatory Culture.” Rethinking Media Change: The Aesthetics of Transition, edited by David Thorburn and Brad Seawell, MIT Press, 2004. Accessed 13 December 2022.

Mamo, Heran. “The Weeknd, Drake, Nicki Minaj & More Artists Who Have Called Out the Grammys.” Billboard, 24 March 2022, https://www.billboard.com/music/awards/artists-calling-out-grammys-9543230/. Accessed 13 December 2022.

McKinney, Kelsey. “The Grammy voting process is completely ridiculous.” Vox, 15 February 2016, https://www.vox.com/2015/2/4/7976729/grammy-voting-process. Accessed 13 December 2022.

Mier, Tomás. “Drake Disses Music Critic Anthony Fantano Over Fake DM Video With a Real, ‘Salty Ass’ Message.” Rolling Stone India, 20 September 2022, https://rollingstoneindia.com/drake-disses-music-critic-anthony-fantano-over-fake-dm-video-with-a-real-salty-ass-message/. Accessed 13 December 2022.

The Recording Academy. The Recording Academy – GRAMMY | .MUSIC (DotMusic), .music, https://music.us/supporters/recording_academy_grammy/. Accessed 13 December 2022.

r/MacMiller. “F*** the grammys.” Reddit, 4 April 2022, https://www.reddit.com/r/MacMiller/comments/tvubif/fuck_the_grammys/. Accessed 13 December 2022.

videogamedunkey. “Game Critics.” YouTube, 8 July 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lG2dXobAXLI. Accessed 13 December 2022.